Chris Ogren stands in a frustrated hunch at a window of New York University’s financial aid office, where he’s come for the fifth time in two days to sort out a problem with his $45,000 worth of student loans.

It gives him little comfort to learn that U.S. universities and colleges are handing $5.3 billion in financial aid this year to students who the government says don’t need it, according to new figures from the College Board, while another nearly $4 billion in tax credits meant to help Americans pay tuition went to families with incomes between $100,000 and $180,000.

More money for higher-income families means less help for lower- and middle-income ones, education experts say. And, in fact, the share of financial aid being given to low-income students like Chris Ogren, who are falling deeper and deeper into debt, has declined steadily over the last 10 years, government statistics show.

“It just doesn’t make any sense,” said Ogren, a 20-year-old junior. “You don’t give the bloated guy the cheeseburger when the starving man is starving.”

The news comes at a time when universities are being stretched by budget cuts and endowment shortfalls. It also follows separate announcements that student debt among low- and middle-income students continues to rise, and income inequality in the United States is getting worse.

“Here we are in a situation where we’ve raised tuition tremendously, the income distribution is more and more unequal, lots of people really can’t afford this, and we are giving a lot of the money to people who could be fine without it,” said Sandy Baum, a higher-education analyst and consultant who collected the statistics for the College Board.

Baum found that colleges and universities awarded $5.3 billion worth of grants beyond the demonstrated financial need of students and their families this year—including state-supported public universities, which in some cases gave more than half of their aid to students who federal formulas showed didn’t need it. Such money, called “merit aid,” is typically given to students based on academic or extracurricular achievements in high school, not based on demonstrated financial need.

“That’s money that goes to students either who have no financial need, or who already have grant aid to meet that need,” Baum said. “They’re not giving [money] only to students who can’t afford to pay, and I think that’s a really important public-policy issue. The state—no matter what the level of funding is—owns and runs these institutions with a social purpose, and asking the question of whether this financial-aid strategy is consistent with that social mission is important.”

About two-thirds of students now have to borrow money to pay for college, and the Project on Student Debt reports that they graduate owing an average of $25,250.

It’s not possible to know from the College Board data whether more money for higher-income students has meant less money for families that are stretching, and borrowing, to pay for college, but experts say that is probably the case. Whatever the cause, the share of financial aid that is going to low-income students has declined steadily over the last 10 years, according to government statistics.

“I don’t have a smoking gun that says for every dollar that goes to [merit aid], there’s a comparable decrease in need-based aid,” said Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation who writes about education. “But it’s fair to say that, given limited resources, low-income students are likely to lose out. And instead we’re talking about providing benefits to students who would almost certainly go to college without this aid.”

Collectively, U.S. universities and colleges supply $24 billion a year in grant aid to their students. The federal government puts another $36.6 billion into higher-education grants, but the government money is restricted to low-income students.

One of the reasons universities are giving money to families beyond the level of need, according to financial-aid directors and independent observers, is to lure applicants with high grade-point averages and SAT scores—who often come from affluent communities wit top-ranked school systems—which elevates the institutions’ standings in all-important college rankings. Public universities also leverage the money to keep talented students from leaving their home states to go to college elsewhere.

“We’re taking those dollars and using them to get richer kids with higher SAT scores to come to a particular institution,” Baum said.

A separate report released earlier this year by the government’s National Center for Education Statistics, or NCES, showed that public universities now give merit aid to more of their students than they give need-based aid. Private universities give merit aid to about the same proportion of students as receive need-based aid.

That’s a shift from a decade ago, when more students at all kinds of institutions got more financial aid based on need than merit. The average merit grant then was smaller than the average need-based grant; now it’s bigger, even though college costs are significantly higher and need is greater.

The percentage of students whose families are in the top 25 percent of earners but who nonetheless get financial aid in the form of merit grants from universities has increased, too, from 23 percent a decade ago to 28 percent today, the NCES found, while the proportion in the bottom quarter of earners fell from 23 percent to 20 percent.

“Schools compete with each other to attract talented students, and in the United States part of our legacy is that the quality of your academic credentials coming out of high school [is] positively correlated with your income,” said Catharine Hill, president of Vassar College and a higher-education economist. “If you want to recruit some of those kids, one way to do it is through merit aid.”

Kahlenberg is more blunt. “Universities compete based on prestige, so if they want to increase their rankings in U.S. News & World Report, an easy way to do that is to bribe high-scoring students to come to your university with non-need-based aid,” he said. “We’re talking about a competition between states and between institutions for competitive advantage.”

The shift in handing out merit aid has resulted from a complicated formula under which the universities presume that offering at least some financial aid to wealthier families will persuade them to enroll and write a check for the rest of the tuition. Even with a generous grant, one higher-income student yields more net revenue than several low-income students.

“That’s a fairly significant percentage of what’s happening, especially for universities and colleges that operate on a tight margin and where tuition revenue is an important part of keeping the lights on,” said Jonathan Burdick, dean of financial aid and admissions at the University of Rochester. “In those circumstances, giving $5,000 against a $25,000 tuition charge is just like the discounting you’d see in a retail operation to bring traffic to the door.”

Universities say they also have been forced to pay out more aid to people who don’t need it thanks to widely publicized changes in financial-aid policies introduced in recent years by highly selective universities including Harvard, Yale and Stanford, which raced one another to give grants to families with income as high as $200,000.

The “war between the haves and the have-lots,” as Brown University dean of admission James Miller wryly described it, ended up with families that earn as much as $100,000—and, at Harvard, $120,000, and Yale, $130,000—no longer having to pay any tuition, and those that make as much as $180,000 (or at Yale, $200,000) being asked to pay an amount equal to no more than 15 percent of their incomes.

The universities said this new approach protects their students from having to take out loans. But by dramatically raising the cap, they set up an expectation among all levels of affluent applicants that they should qualify for grant aid, too, putting pressure on less-selective universities and colleges to offer support to families that don’t necessarily need it.

“The Ivies have a disproportionate effect on people, and they started saying things like, ‘nobody should have to borrow for an undergraduate education,’ ” Burdick said. “They also said that middle income is $200,000 and more, so they have sharply cut what those families expect to have to pay. It’s all well-intentioned, but what it has done is fuel a situation where families with high incomes are moving to the best bidder.”

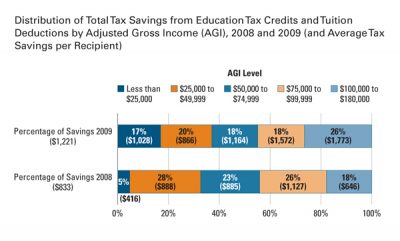

Those high-earning families are also now enjoying tax breaks toward tuition under the American Opportunity Tax Credit, the income eligibility for which was raised to $180,000 in 2009, and which has been extended until December 31, 2012. The credit cost the treasury $14.7 billion in 2009, the most recent year for which the figures are available. That’s twice what it cost in 2008, and the proportion of the credits that went to families making more than $100,000 rose from 18 percent to 26 percent.

“People just don’t understand that the federal government is handing money to families with incomes up to $180,000,” Baum said. Kahlenberg called it “an almost silent, little-noticed increase for fairly wealthy individuals.”

Others pointed out that because college costs have increased so much, even families earning $100,000 or more are having trouble paying for it, especially with more than one child at a time enrolled.

“You have an inflated housing market, so mortgages are eating up a large part of people’s incomes,” said David Hawkins, public-policy director at the National Association for College Admission Counseling. “Even $100,000 is being stretched to the limit.”

But Hill said the shift in grant aid was “consistent with what’s happening with the income distribution issues in this country right now. The tax benefits are really now hitting that higher-income bracket. We have to ask: Are those students who wouldn’t be making it to college otherwise?”

Nick Pandolfo contributed reporting.

A version of this story appeared in USA TODAY on November 25, 2011.

Tuition has been raised 2%-3% more than needed each year for more than 20 years. Students at the bottom of the admissions list who can afford to pay get no scholarship money and their added tuition payment goes as scholarships to the students at the top of the list. In affect, the poorer students are financing their competition for employment and graduate school. See

http://www.textbooksfree.org/Interesting_Thoughts_Concerning_Education.htm#Why_College_Tuition_is_Not_Going_Up_Rapidly

Just because people make $100,000 – $180,000 annual income doesn’t meant they have the money to actually afford college.

Depending on where they live, living costs, how many people they are providing for, etc.

You can’t just assume people who work hard and make money, actually have money, like $50,000 to put towards a year of college for four consecutive years or more.